In 1937, Pablo Picasso finished one of his greatest and best-known works—Guernica. The massive black-and-white painting is over 11 feet tall and 25 feet wide.

The secret to originality?

Focus on choices, not end goals.

The story behind Guernica is well known. The painting was commissioned for the World’s Fair in Spain but was inspired by the Nazi’s complete and horrifying destruction of the town that bears the same name.

The destruction came at Spain’s ruling party’s request because Guernica was not just a center of Basque culture—but also a stronghold of the Republican resistance movement.

“A hodgepodge of body parts that any

four-year-old could have painted.”

— A review of Picasso’s work in a 1937 German guidebook

for Paris’s International Exposition.

Despite the dismissive critique in the above quote, Guernica’s impact and significance extend far beyond its initial reception. The painting is a testament to the power of art as a medium for political and social commentary.

After the town of Guernica was nearly annihilated (one-third of the population was killed or wounded in just three hours), Picasso spent around five weeks trying to capture the event in his painting.

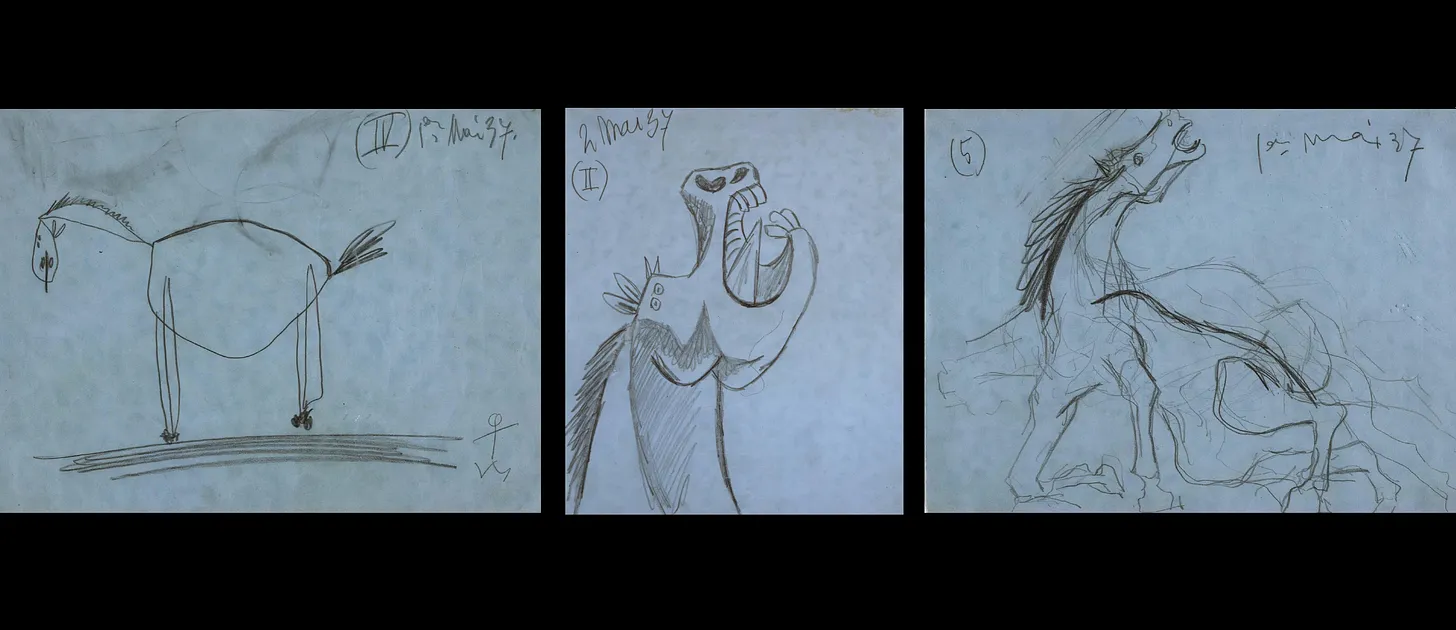

Below, you see one of the many sketches exploring the painting’s central figures and metaphors.

The bull, dying horse, and mother with the dead child are all in the final painting, but they have evolved from the image you see here.

Picasso meticulously dated drawings and paintings—hundreds of sketches and studies, each marking a point in his journey. This process was not a straight path but a web of exploration and decision-making.

Picasso—who rarely allowed strangers into his studio to watch him work—opened his doors for Guernica, inviting influential visitors to observe his progress. This was a strategic move, aiming to raise awareness for the resistance.

“Did you do that?” a German Gestapo officer asked while pointing

at a photograph of Picasso’s painting.

“No, you did,” Picasso replied.

One observer, Dora Maar, captured 28 photographs of the painting as it developed and changed between May and June. In a photo taken by Maar (below), Picasso is shown painting, holding a long brush, feather duster, and cigarette simultaneously.

These photographs are not just a record of an artwork; they are a visual narrative of a creative process that was anything but linear.

So are the following drawings, which represent three out of many studies for a horse.

Compare the childlike stick figure drawing on the left with the energetic, more realistic collapsing horse on the right. The center drawing focuses on the expression.

Academic studies of Picasso’s process affirm what many creators suspect: the journey to a final creative solution is seldom straight. It’s a path that meanders, backtracks, and leaps forward in unexpected ways.

In fact, many elements in Guernica were revised, dismissed, and then reintroduced.

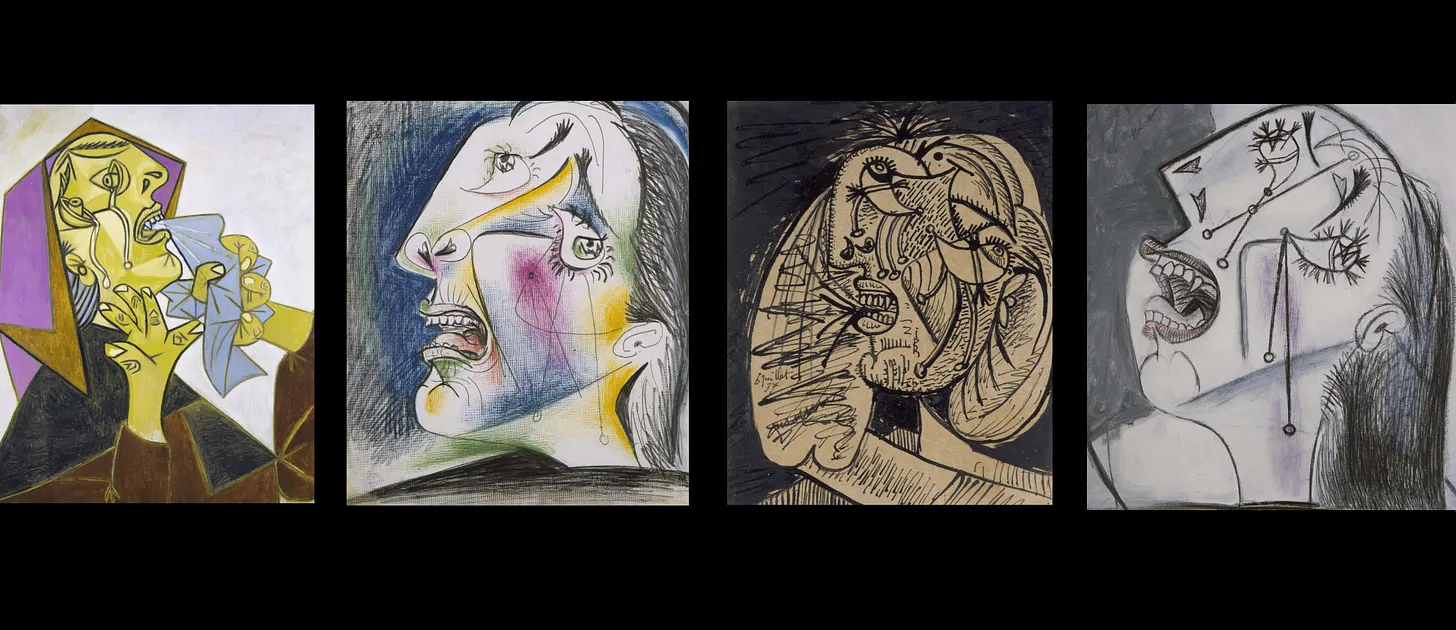

For example, many of the early preparatory studies explore color. The following two color drawings show this exploration in progress:

At a later point, Picasso tested color—red teardrops and other highlights—on the final canvas only to simplify and discard them.

The final painting is famous for its lack of color. Yet, the path Picasso took to get to the grey, black, and white scene we know today was through color.

“A painting is not thought out and settled in advance.

While it is being done, it changes as one’s thoughts change.

And when it’s finished, it goes on changing,

according to the state of mind of whoever is looking at it.”

— Pablo Picasso

Picasso also explored a wide range of ideas to capture the suffering in the woman’s expression. The images have the same elements—an upward glance, tears, a wailing mouth—that vary greatly in expression.

The simplified wailing woman in the final painting owes much to these more complex early studies. Would Picasso have chosen his final direction if he had not first explored so widely?

As creatives, we do well to accept that our own processes should be messy—full of explorations that include false starts, dead-ends, and direction changes that circle back to past variations and incorporate unexpected connections.

Experimentation and revision are necessary for creative work.

The biggest challenge in achieving originality, as Picasso’s process illustrates, is not just in finding inspiration or generating ideas. It’s in the choices you make and how you navigate the myriad possibilities that arise in your creative journey.

Embrace this process with the understanding that each step, whether it feels like progress or not, is a crucial part of your creative evolution. Your willingness to explore, discard, and embrace change will lead you to find original and effective solutions.

Remember, as a creator, your path doesn’t need to be predictable or smooth. It’s in the unpredictable, the trials and errors, that true creativity is often found.

Let Picasso’s Guernica remind you that your unique journey, with all its diversions and detours, is not just a path to originality but a testament to the creative spirit.

SOURCE: Originally published in Creative For Creatives on Substack.